The new hull for Edna Lockwood was placed directly next to the 1889 bugeye in July, allowing shipwrights to prepare to marry it with her existing topsides this fall.

Check out this (sped up) video to watch her move and then come see for yourself!

The new hull for Edna Lockwood was placed directly next to the 1889 bugeye in July, allowing shipwrights to prepare to marry it with her existing topsides this fall.

Check out this (sped up) video to watch her move and then come see for yourself!

It was bottom's up on April 11, 2017, for the Edna E. Lockwood, the last historic bugeye to sail the Chesapeake Bay. Shipwrights at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, MD, are replacing the hull of the grand old lady so she can once again sail the Bay. Restoration will continue until the fall of 2018, when she will be ceremonially launched during the annual Oysterfest.

Video by Sandy Cannon-Brown

Descendants of John B. Harrison, the builder of 1889 bugeye Edna E. Lockwood, visited the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum on Friday, April 14, 2017, to see the vessel created by their family member.

While at CBMM, the family learned about Edna Lockwood and her historic restoration from Boatyard Manager Michael Gorman.

Shipwrights and apprentices recently began pinning together logs for Edna Lockwood's new hull as part of her historic 2016-2018 restoration. Here, we give you a short lesson on the process.

Shipwrights at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, MD are restoring the log-built hull of the historic bugeye Edna E. Lockwood. Built in 1889 on Tilghman Island, Edna is so important and rare that she was named a National Historic Landmark. The restoration will be completed by October 2018 when Edna sets sail again during Oysterfest 2018 at the museum. The public is invited to come watch her restoration in progress.

Video by Sandy Cannon-Brown

(ST MICHAELS, MD – January 17, 2017) Shipwrights and apprentices at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum have identified all nine of the loblolly pine logs to be used in on the 2016-2018 log-hull restoration of the historic 1889 bugeye Edna E. Lockwood.

“We’re very excited to have the final logs selected for this once-in-a-lifetime restoration,” said CBMM Boatyard Manager Michael Gorman. “Things are really starting to come together.”

The team is restoring CBMM’s queen of the fleet and National Historic Landmark Edna E. Lockwood by replacing her nine-log hull, in adherence to the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Historic Vessel Preservation. Shipwright apprentices working on the project are generously supported by the Seip Family Foundation and the RPM Foundation. All work takes place in full public view at CBMM’s waterfront campus on the Miles River in St. Michaels, Md., now through 2018.

In March 2016, 16 loblolly yellow pine logs measuring more than 3-foot in diameter and over 55-foot long were delivered to CBMM after a two-year search, thanks to a very generous donation by Paul M. Jones Lumber Co. of Snow Hill, Md. With transportation costs of the logs underwritten by individual donors, the pine logs were trucked to St. Michaels by Johnson Lumber of Easton, Md., and submerged in the Miles River for preservation. This fall, the logs were moved onto the sawmill and rough-shaped as the crew began to identify which logs would be selected for the hull.

“It was very important to us to choose the right logs for this project,” Gorman said. “We were looking for old trees with tight grain, and we’re really happy with our results so far.”

Over the rest of the winter, shipwrights and apprentices will be preparing molds for the outside shape of Edna’s hull, constructing her three cabins inside the boatshop, and continuing to shape and pin logs. The beginnings of the hull are on display now in the boatyard.

Through spring 2017, the new log hull will be assembled and the original four frames present in the bugeye will be located and installed to reinforce the hull. When the restoration is complete, Edna will be placed on the marine railway and re-launched at CBMM’s OysterFest in 2018.

Built in 1889 by John B. Harrison on Tilghman Island for Daniel W. Haddaway, Edna Lockwood dredged for oysters through winter, and carried freight—such as lumber, grain, and produce—after the dredging season ended. She worked faithfully for many owners, mainly out of Cambridge, Md., until she stopped “drudging” in 1967. In 1973, Edna was donated to the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum by John R. Kimberly. Recognized as the last working oyster boat of her kind, Edna Lockwood was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1994. Edna is the last historic sailing bugeye in the world. More about the project, including progress videos, is at ednalockwood.org.

Established in 1965, the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is a world-class maritime museum dedicated to preserving and exploring the history, environment, and people of the entire Chesapeake Bay, with the values of relevancy, authenticity, and stewardship guiding its mission. Serving more than 75,000 guests each year, CBMM’s campus includes a floating fleet of historic boats and 12 exhibition buildings, situated in a park-like, waterfront setting along the Miles River and St. Michaels’ harbor. For more information, visit cbmm.org.

Take a quick look at some of the sights and sounds from the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum's boatyard over the past few months as work continues on the historic restoration of 1889 bugeye Edna E. Lockwood.

This fall, logs have been moved onto the sawmill and rough shaped as the crew begins to identify which will be a part of the Edna E. Lockwood's new hill. Over the winter, logs will continue to be shaped and pinned together with traditional tools, like the adze. By the end of spring 2017, the new log hull will be assembled and the original four frames present in the bugeye will be located and installed to reinforce the hull. Visit CBMM in St. Michaels, Md., to watch as the progress unfolds.

The boatyard is abuzz with activity now through 2018 on the historic restoration of the Queen of our fleet, the 1889 nine-log-bottom bugeye, Edna E. Lockwood. Today, CBMM Boatyard Manager Michael Gorman uses a chain saw to shape one of the logs that will form Edna's new hull. Come visit our boatyard and witness the transformation firsthand.

On Wednesday, May 4, 2016, the historic 1889 log bottom bugeye Edna E. Lockwood was moved by crane off of the marine railway and up on the hard in preparation of the historic restoration of her nine-log hull. Come see the queen of the fleet and the logs that will replace her hull at CBMM and learn more at ednalockwood.org.

See high resolution photos here on our Flickr Page:

On March 10-11, 2016, we hosted a symposium of historic vessel preservation experts, allowing a detailed examination of proposed procedures and recommendations for the restoration of Edna E Lockwood. Symposium experts were:

· John Brady, President, Independence Seaport Museum

· Todd Croteau, Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service

· Richard Dodds, Curator of Maritime History, Calvert Marine Museum

· John England, Head Shipwright, Deltaville Maritime Museum

· Quentin Snediker, Shipyard Director, Mystic Seaport Museum

· George Surgent, Head Shipwright, Calvert Marine Museum

Our principal take-aways from the forum were:

1. Fundamentally, our approach of assembling new logs separately, cutting the bottom off the existing boat, and marrying new with existing, is sound. This approach has a number of advantages: it maintains the historic continuity of the boat, as recognized in historic preservation best practice, so that even with 100% material replacement, we still have the historic vessel (as identified by Snediker). By assembling the new logs separately (as opposed to a piece-by-piece replacement), original fastening techniques can be replicated (as pointed out by Michael Gorman and vetted by others). And this approach also allows us to save a significant part of the historic material in an intact and recognizable form--something that is rarely accomplished in historic vessel preservation projects, unless the old vessel is mothballed to an interior space and replicated afloat.

2. We were encouraged to make use of traditional sealants—raw linseed oil, turpentine, red lead—and to avoid epoxies and plastics.

3. We heard an extensive discussion on fasteners, which steered us away from steel and toward a combination of bronze and locust or Osage treenails.

4. We have unanimous support for attempting to remove the hog (drooping of the ends), but it comes with a number of cautions about how to adequately plan for this, which will mean a bit more with adjusting the HAER drawings and problem-solving with how the old is married to the new.

5. The interior of the vessel provides little opportunity for interpretation, so the guiding principle should be to maximize air circulation below decks, an important factor in long-term preservation.

6. We seemed to arrive at a consensus to select a mid-20th century date for the restoration period; that is, when the project is completed, Edna should appear much as she did at the end of her oyster dredging days, and that date should guide decisions about what to include when there are possible options.

Our plans for Edna through September—before we start work on the logs—have taken an interesting turn. She was to be put back in the water, to clear the railway for Winnie Estelle to be prepped for her Coast Guard inspection. Unfortunately, one of Edna’s logs has rotted out and she’ll need to stay dry. We have a 100 ton crane arriving this week to remove her masts and to lift her parallel to the waterfront container that is acting as her workshop. We’ll make this work on our behalf, as we plan to build access steps up to Edna’s deck, and from the deck guests will be able to see the logs being worked on.

-Kristen Greenaway, CBMM President

(ST. MICHAELS, MD–February 22, 2016) On Friday, March 11, 2016, the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, Md. will convene a panel of maritime preservation experts for a public forum on its planned 2016-2018 restoration of the National Historic Landmark Chesapeake Bay bugeye Edna E. Lockwood. The program runs from 9:00 to 12:00 noon in the museum’s Van Lennep Auditorium with a panel that includes specialists in wooden vessel restoration, maritime documentation, and historic vessel preservation. The forum is free and open to the public, with limited seating and advanced registration required.

Participating on the panel will be John Brady of Independence Seaport Museum, Todd Croteau of the National Park Service Maritime Program, Richard Dodds of Calvert Marine Museum, John England of Deltaville Maritime Museum, Quentin Snediker of Mystic Seaport Museum, and George Surgent of Calvert Marine Museum.

The session opens at 9:00 a.m. with an introduction to the 1889 Tilghman-built oystering vessel, Edna E. Lockwood, which has been a floating exhibition at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum since 1967. Later in the forum, the panel will review the recent documentation of Edna’s hull through photogrammetry and laser scanning, followed by an overview of what lies ahead in the restoration project. The panel will address a series of questions and technical problems anticipated in the restoration, with the public invited to ask questions and offer comments.

Built in 1889 by John B. Harrison on Tilghman Island for Daniel W. Haddaway, Edna E. Lockwood dredged for oysters through winter, and carried freight—such as lumber, grain, and produce—after the dredging season ended. She worked faithfully for many owners, mainly out of Cambridge, Md, until she stopped “drudging” in 1967. In 1973, Edna was donated to the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum by John R. Kimberly. Recognized as the last working oyster boat of her kind, Edna E. Lockwood was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1994.

“This type of boatbuilding is specific to the Chesapeake Bay,” said CBMM Chief Curator Pete Lesher. “Just as Native American dugout canoes were formed by carving out one log, a bugeye’s hull is unique in that it is constructed by hewing a set of logs to shape and pinning them together as a unit. Over the next two years, museum guests will have incredible opportunities to watch the restoration progress and to see a boat built in a way you can find nowhere else, and in full public view.”

Established in 1965, the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is a world-class maritime museum dedicated to preserving and exploring the history, environment and people of the entire Chesapeake Bay, with the values of relevancy, authenticity, and stewardship guiding its mission. Serving more than 70,000 guests each year, the museum’s campus includes a floating fleet of historic boats and 12 exhibition buildings, situated on 18 waterfront acres along the Miles River and St. Michaels’ harbor. To register for the March 11 forum, email aspeight@cbmm.org or call 410-745-4941.

“CBMM_Forum_EdnaLockwood.jpg”

The 1889 log-bottom bugeye Edna E. Lockwood, shown here, is the queen of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum’s fleet of historic Chesapeake boats and will be the focus of a March 11 public forum when CBMM convenes a panel of maritime preservation experts to discuss Edna’s planned restoration. Recognized as the last working oyster boat of her kind, Edna E. Lockwood was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1994. The March 11 program runs from 9:00 to 12:00 noon in the museum’s Van Lennep Auditorium, and is free and open to the public, with limited seating and advanced registration required. More photos of the bugeye are atbit.ly/ednarestorationphotos.

On March 5, 2016, delivery of the loblolly pine logs needed for the restoration of the nine-log bottom hull of the 1889 bugeye Edna E. Lockwood- the last historic log-bottomed bugeye still under sail-took place at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, Maryland.

The 1889 log-bottom Chesapeake bugeye Edna E. Lockwood's loblolly pines logs have been secured after a two year search, thanks to a very generous donation by Paul M. Jones Lumber Co. of Snow Hill, Md.

On the morning of March 5, 2016, delivery of the loblolly pine logs needed for the restoration of the nine-log bottom hull of the 1889 bugeye Edna E. Lockwood— the last historic log-bottomed bugeye still under sail—took place at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

With transportation costs of the logs generously underwritten by individual donors, the pine logs are being trucked to St. Michaels, and will be submerged in the Miles River for preservation until the restoration project continues later this year.

Johnson Lumber of Easton, Md. is delivering 16 logs—allowing overages if needed for the project—with the logs averaging 55-feet in length, and a 10-foot circumference.

On March 5, 2016 the logs needed for the restoration of the historic bugeye Edna E. Lockwood were delivered to the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. We were there.

The 1889 log-bottom Chesapeake bugeye Edna E. Lockwood's loblolly pines logs have been secured after a two year search, thanks to a very generous donation by Paul M. Jones Lumber Co. of Snow Hill, Md. On the morning of March 5, 2016, delivery of the loblolly pine logs needed for the restoration of the nine-log bottom hull of the 1889 bugeye Edna E. Lockwood— the last historic log-bottomed bugeye still under sail—took place at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

With transportation costs of the logs generously underwritten by individual donors, the pine logs are being trucked to St. Michaels, and will be submerged in the Miles River for preservation until the restoration project continues later this year.

Johnson Lumber of Easton, Md. is delivering 16 logs—allowing overages if needed for the project—with the logs averaging 55-feet in length, and a 10-foot circumference.

On February 29, 2016, the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum had the pole shed demolished in the boatyard. The building has to be removed to make room for the historic 2016-2018 restoration of the 1889 bugeye Edna E. Lockwood. Shipwrights and volunteers salvaged as much of the wood before the demolition. The building was built as a temporary structure more than 30 years ago, and suffered rot and termite damage in much of the timbers. Learn more about the historic restoration of the log-built 1889 bugeye Edna E. Lockwood, a National Historic Landmark as the last of her kind, and the queen of the Museum's fleet at bit.ly/ednalockwood.

Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum Boatyard Manager Michael Gorman, along with his apprentices and volunteers, have hauled out the 1889 nine log bottom bugeye Edna E. Lockwood this winter to make room for the National Park Service to laser scan and photograph the historic boat’s log hull.

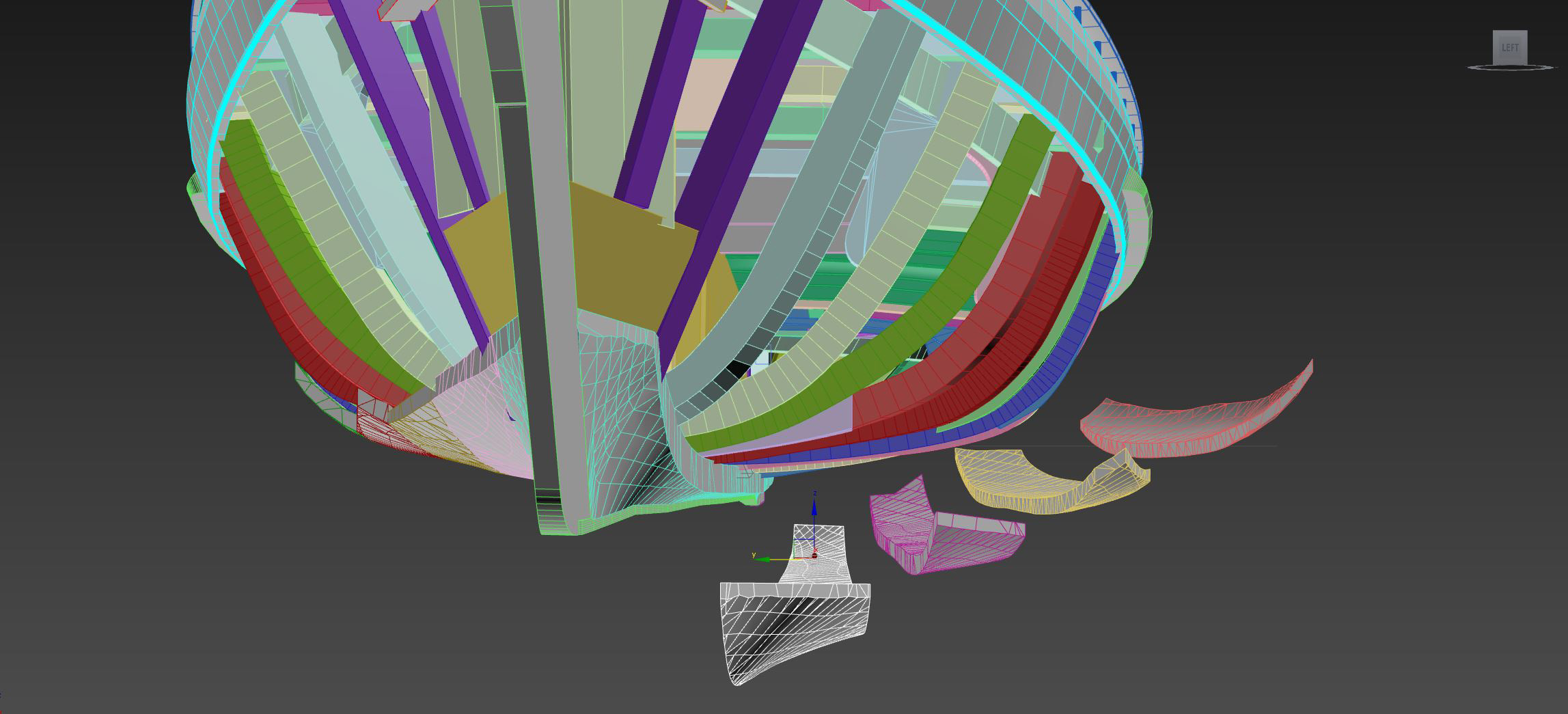

The information is being put together by NPS’s Heritage Documentation Programs to document the different parts of the hull and how they come together as a greater whole. The project is part of the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) Maritime Documentation Program, with the produced measured drawings added to the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection in The Library of Congress to document the last working oyster boat of her kind. For CBMM, the information gained will be turned into a 3D model to aid museum shipwrights and apprentices in the restoration of the Edna E. Lockwood.

The nine logs making up the historic bugeye’s hull are in need of replacement, with the restoration project planned to begin in late 2015. Just as Native American dugout canoes were formed by carving out one log, this bugeye’s hull is constructed of a series of pinned logs shaped and hollowed out as a unit.

In 1889, at the age of 24, John B. Harrison of Tilghman Island built the Edna E. Lockwood, the seventh of 18 bugeyes he was to build. Harrison also built the log canoes Flying Cloud and Jay Dee.

Built for Daniel W. Haddaway of Tilghman Island, Edna E. Lockwood dredged for oysters through winter, and carried freight—such as lumber, grain, and produce—after the dredging season ended. She worked faithfully for many owners, mainly out of Cambridge, MD, until she stopped “drudging” in 1967. In 1973, Edna was donated to the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum by John R. Kimberly. Recognized as the last working oyster boat of her kind, the Edna E. Lockwood was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1994.

The museum continues to look for help in sourcing the southern yellow pine logs required to begin replacing Edna’s log bottom. Twelve logs measuring 52’ in length and 3-4’ in diameter are needed.

To see video of the NPS at work on the Edna E. Lockwood, visitwww.bit.ly/Edna_NPS. For more information on the Edna E. Lockwood, visit www.cbmm.org.